Spore Killing Genes (Spoks)

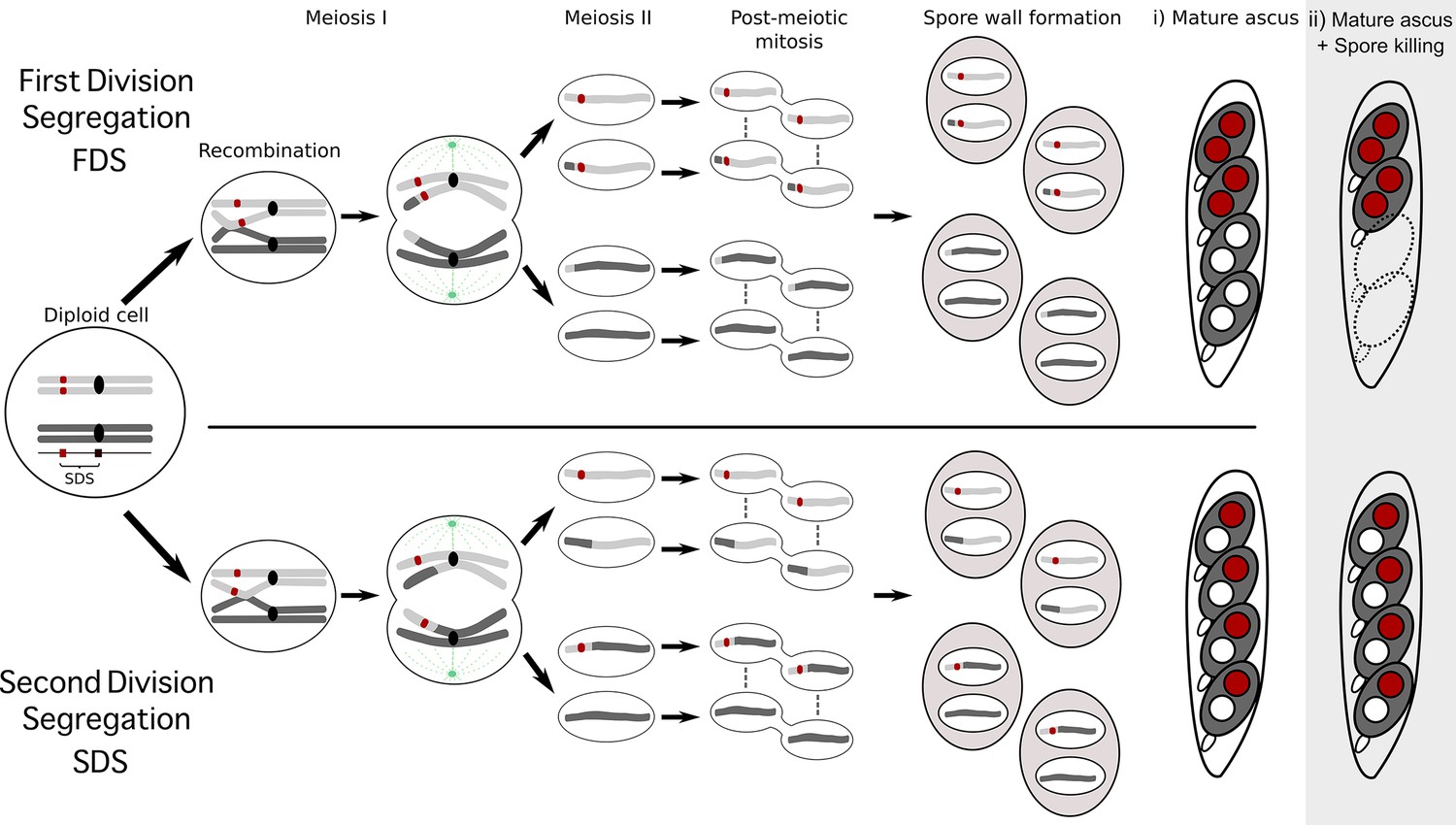

According to Mendel’s law of segregation, in a diploid organism the two copies of a gene are equally likely to be passed on to the next generation. Exceptions to this are, however, common. Recent work into one such exception, namely the spore killing genes (Spoks) of Podospora anserina , has begun to unravel how these genes are able to kill any offspring cell that does not carry them (Vogan et al. 2019). By genetically transforming Podospora with either full or partial copies of the Spoks, the researchers have been able to deconstruct the protein product into a toxin and an anti-toxin domain. Not only do several variants of Spoks exist in P. anserina , but homologs of these genes in unrelated fungal species abound. Interestingly, many diverged homologs of the Spok genes are found within the fungal genus Fusarium . We call the Spok-homologs found in this genus FuSpoks. Fewer than 20% of Fusarium species are known to have a sexual cycle. The question thus arises, what role the FuSpoks may have in asexual species?

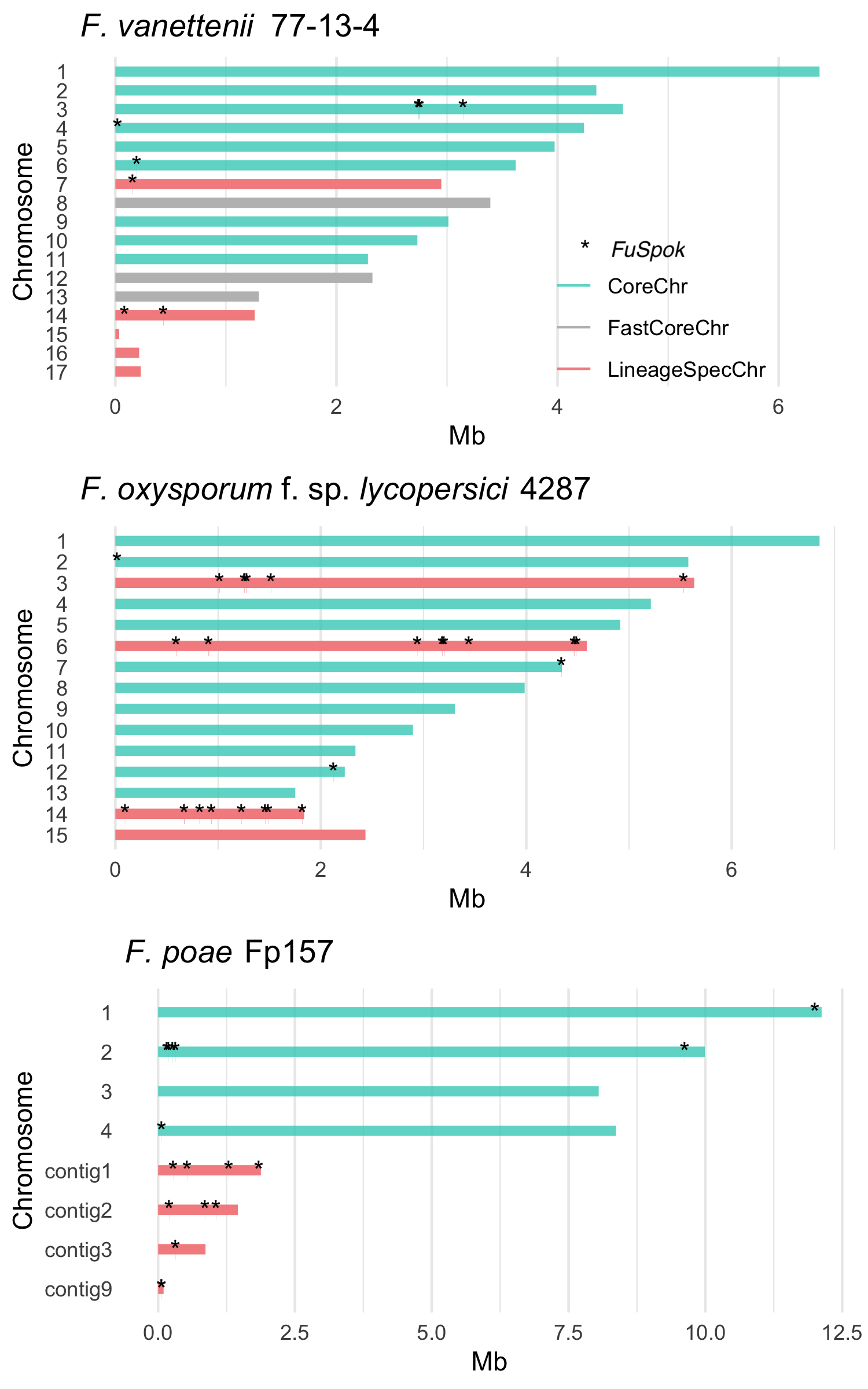

The Fusarium fungi are known to be successful plant pathogens with a highly malleable genome. In addition to a set of core chromosomes, each isolate of a particular Fusarium species may carry a number of additional chromosomes. These extra chromosomes are referred to as Lineage Specific, Conditionally Dispensable, or Accessory. The accessory chromosomes often carry effector genes that help the fungi infect its host. In a seminal paper, Li-Jun Ma and colleagues (2010) demonstrated the horizontal transfer of accessory chromosomes between different strains of F. oxysporum . When mapping the FuSpoks onto Fusarium genomes, they are found in the accessory regions (either telomeric regions that are known to be rapidly lost and gained, or on the accessory chromosomes themselves). We have tentative evidence that accessory chromosomes that carry FuSpoks are lost less frequently compared to accessory chromosomes that do not carry FuSpoks, suggesting that these genes may act as selfish elements even during asexual reproduction.

To test our hypothesis we use a multi-pronged approach. Using bioinformatics, we investigate at the evolutionary history and phylogenetic distribution of FuSpoks: rapidly expanding gene families are more likely to be actively driving elements. Meanwhile, in the laboratory, we investigate whether candidate genes have functional toxin and resistance domain, similar to the Spoks described in Podospora. We do this by expressing full copy and mutated versions of different FuSpoks in yeast, following the approach of Urquhart & Gardiner (2023).